The Identity Classification Bureaus In Our Heads

Part of our But Where Are You Really From? season

If I were to make a ‘But Where Are You Really From?’ version of Inside Out, Pixar’s beautiful ode to the emotions that drive us, it would include a new personality island called the Identity Classification Bureau (ICB). In the film, 11 year old Riley goes through a relocation of cities creating stirring interactions between her emotions and five personality islands of family, friendship, honesty, goofball and hockey. Each personality island has a history and purpose of its own, as will the ICB.

© Smriti Parsheera via Canva.com

Inside the ICB, rows of tiny identity agents work tirelessly to label, classify and file all our encounters into pre-marked identity cabinets. Buzz! New person alert! Ethnicity sorting? Check. Gender label? Check. Language score? Check. And so on. By the time the new entry reaches the end of the assembly line, the ICB knows whether they belong in the 'us' cabinet or the one reserved for 'them' and has a specific slot waiting for them.

But every now and then we come across things that don't fit neatly into our existing identity baskets. The confused ICB then sends out a memo prompting us to ask, but where are you really from?

As a graduate student in the United States, I would sometimes be asked, are you Indian? But you look so Asian!? Americans often use the term Asian to refer only to people belonging to the Far East part of Asia. Think China, Malaysia, Japan, Vietnam, Korea and Indonesia. Someone who is from India but looks more ‘Asian’ than the stereotypical ‘Indian’, therefore, becomes a bit of an oddity.

Years before that, my father was a Masters student at the University of Bradford in England. It was our first experience living outside India but Bradford turned out to be the closest one could be to home while being outside it. Everything from our Gujarati landlord Mr. Mistry to the recognizable names on shop fronts and from the sound of Sunrise Radio to the local video store supplying the latest Bollywood fix lent an air of familiarity to the city.

In school, with the exception of one white student, everyone in my class was of British Pakistani or British Indian origin. Many of them were perplexed by the fact that the only person who was actually from the region did not really look or dress the part. The primary school that I attended did not have a uniform and most of the girls came dressed in salwar kameez, an item of clothing that I did not possess at the time. My mushroom or katora (bowl) haircut that 90s parents loved to inflict on their children also stood out against the long plaited hair worn by the other girls. This led some of my young friends to create a new shelf – for the girl from India who could well be from Japan.

But the workings of the ICB are not always innocent and harmless. For instance, most urban Indians learn early on in their lives to maintain a designated shelf for the ‘chinkis’. This ethnic slur is used to describe people from the North-East region of India and certain other parts like Ladakh and Lahaul-Spiti in Himachal, where I come from, based on their ‘Chinese-looking’ features. It comes handy in everyday acts of labeling, bullying and alienation across schools and colleges, in housing colonies, and on the streets.

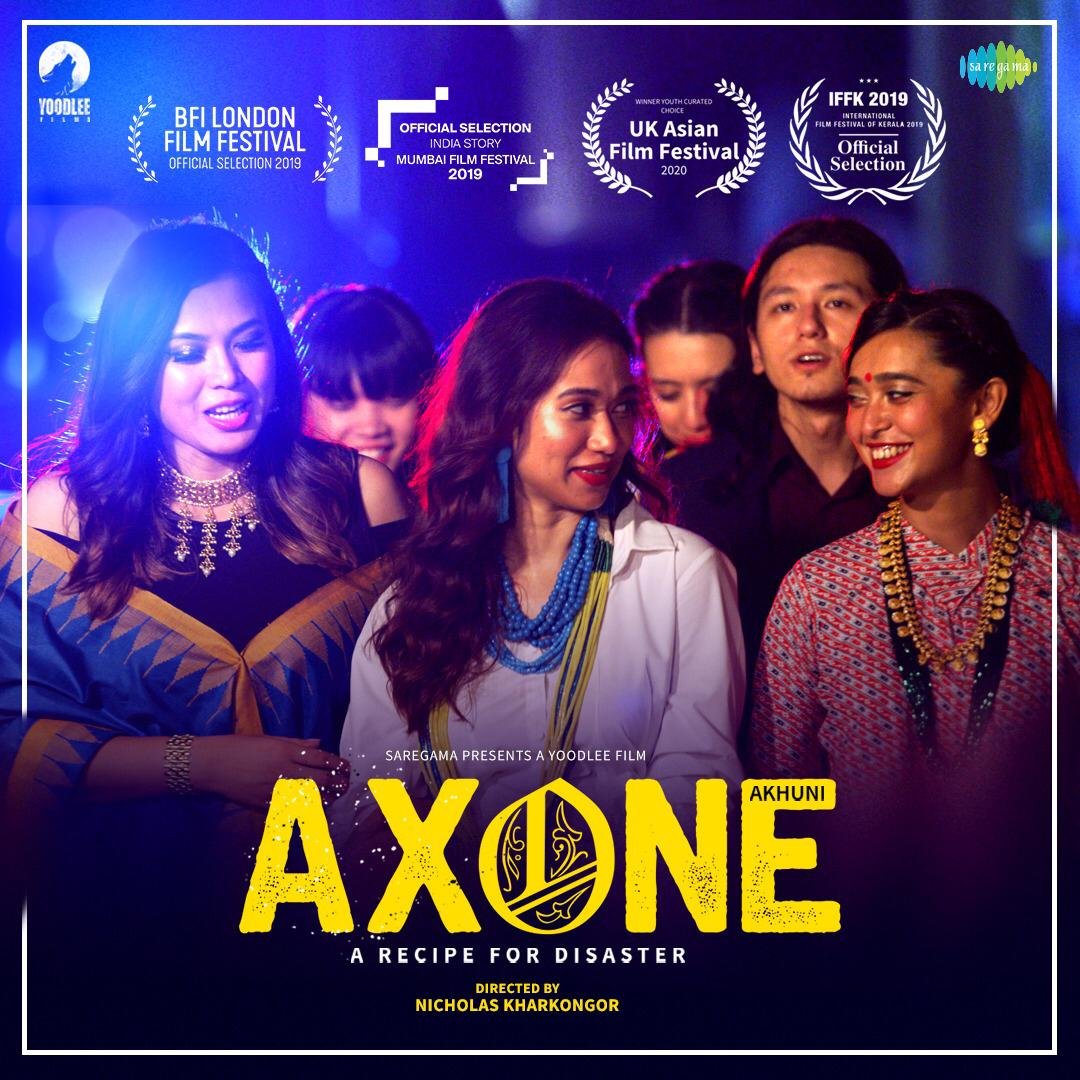

Axone (2019) by Yoodlee Films captures a day in the lives of a bunch of outsiders navigating life in Delhi.

The ICB draws its energy from what we see and the conduct of those around us. Friends who grew up in Indian states like Bihar and Kerala tell me that they had not heard the term chinki being used until they moved to larger cities like Delhi and Bengaluru. They of course had other labels born out of their local context. A friends-sourced list threw up several examples of caste, religion, and region-specific labels from the great Indian ICB database. The term ghati that originally referred to people from the hilly parts of Maharashtra is now used to imply inferiority and ignorance. North Indians are labeled as choms in Bengaluru, while they in turn might classify all South Indians as Madrasis. Some Gujarati girls are mani-bens and working class Tamils in Kerala are pandis.

Media representation serves as fodder for the ICB. The less we see of something the more we are convinced that it does not belong. Most Bollywood aficionados would struggle to think of a film celebrity (other than the Sikkimese actor Danny Denzongpa) who belongs to India's mountain tribes. Characters and stories from these parts are equally rare. And when they do make the cut, the process of othering comes along with it. In a much talked about example, the 2014 biopic on Olympic medalist Mary Kom preferred to paint smaller eyes on the bankable star Priyanka Chopra than risk the authenticity of casting someone who actually looks like the Manipuri boxer.

This makes it unsurprising that Western depictions of Indians, that are anyway few and far between, reflect even less of the country’s diversity. The Office’s Kelly Kapoor, Bend It Like Beckham’s Jess Bhamra, Quantico’s Alex Parrish and Harry Potter’s Padma and Parvati Patil have all helped train many an ICB on what an Indian woman looks like. To then suggest that someone like Katie Leung, who plays Cho Chang in the Harry Potter films, could as easily have fit into the shoes of the Indian twins in the Harry Potter series would shock most fans, and possibly even Rowling herself.

Harry Potter and the Order of the Phoenix (2007), Warner Bros.

While one part of the ICB works furiously to label and classify others, another set of agents help us understand ourselves. In this process, the ICB can sometimes find clues in the most unexpected of places. A few years back, I had a chance to watch the Georgian film Dede at a film festival in Delhi. The stunning landscapes of the remote Ushguli village in the Greater Caucasus Mountains reminded me of my own home district of Lahaul-Spiti in the Himalayas. Visuals of people shoveling snow collected on rooftops and wading through knee deep snow for medical help resonated with stories one heard of winter life in Lahaul.

I also found some other, more intriguing, similarities such as the sight of the rectangular iron stove, which we call the tandoor, being used in every house. And the geometric prints on hand knit socks that were a reminder of our colorful Lahauli socks. I learnt soon after that these traditions were brought over from Europe by the Moravian Missionaries who came to Lahaul towards the end of the 19th century, creating an unlikely identity bond through these shared artefacts.

Dede (2017), Corinth Films

The introduction to Korean dramas opened up yet another window in my mind’s ICB. In 2020, as the world went into lockdown mode, I was part of the cult that took to K-dramas like a religion. The time travelling king, the goblin in search of his wife, the South Korean business woman stuck in the North, and the group of friends growing up in Ssangmun-dong, all became fellow travellers through these uncertain times.

Reply 1988 (2015)

Besides the escapism and the feel-good factor offered by K-dramas, I found this universe to be fascinating for another reason. Fellow overthinkers might relate to the feeling of watching a new film or show accompanied by the nagging itch of trying to figure out, who does this actor remind me of? It's similar to having a tune stuck in your head but not being able to remember the words. My newfound K-drama diet came with the realization that for the very first time I was seeing so many faces in which I could see glimpses of people from my own network -- an aunt’s husband, a distant cousin, a family friend, and so. Making these links was entertaining, no doubt, but also strangely uplifting. This visual relatability might also explain why the K-wave swept through certain parts of India much before it hit the rest.

This year, two of India’s most iconic brands, Amul Butter and the Indian Railways, embraced the K-wave through their shout outs to BTS and Netflix’s Squid Games. It does not get more mainstream than this. But will this appreciation of cultural diversity stop at consumption choices fueled by international trends? Or will India’s evolving entertainment scene eventually nudge a new generation of ICBs into being more aware and welcoming of the diversity within? In a piece that begins with Pixar and invokes K-drama optimism, I can't but hope for this cheerful end.

Smriti Parsheera

Twitter: @SmritiParsheera

This piece is a part of our But Where Are You Really From? season, made possible thanks to the BFI Audience Fund awarding funding from the National Lottery.